Rice’s grandfather, Richard Burton, was a Civil War veteran who escaped slavery to join the Union Army in Tennessee before coming to Dayton and opening up the city’s first Black laundry.

After graduating from Stivers High School, Rice attended Fisk and Wilberforce universities.

He returned to Dayton in 1936 and became a teacher at Dunbar High School, the only school that allowed for Black teachers at the time. He stayed there for 35 years.

In 1973, the city asked Black teachers to volunteer for reassignment in order to break down segregated teaching staffs. Rice volunteered and went to Meadowdale. A year later he retired from the Dayton school system and began teaching at Chaminade Julienne “to keep busy.”

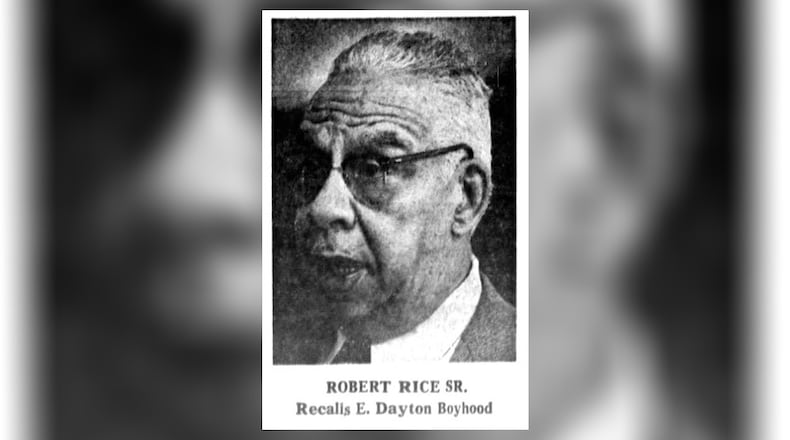

Rice spent a lifetime collecting written and oral Black history from the area. A 1974 Dayton Daily News article called Rice a “talking history book.”

Over the years, Rice was interviewed and wrote columns for the Dayton Daily News many times. Here are some of the facts and stories he shared with us.

First Black residents arrive in Dayton

According to Rice, the first Black residents came to Dayton between 1796 and 1798, a year or two after white settlers arrived.

Several thousand people are believed to have made their way into Ohio as squatters prior to the official settlement of the region in the 1790s and there were Black residents — probably escaped slaves — among them.

The name of the very first Black resident is lost to history, but he is described as a servant of the family of Daniel Cooper, proprietor of the town.

In 1803, Cooper brought a second Black person, a girl who worked as a servant, to a farm south of the town. Shortly after arriving, she gave birth to the first Black child here and named him Harry Cooper, taking her employer’s family name.

The earliest Black settlement was downtown and on the East Side, in an area called Seely’s Ditch.

When the village officially became a city in 1841, there were about 400 Black residents out of a total population of 5,000.

Paul Laurence Dunbar

Rice liked to set the record straight on Black history in the city. One common error he cited was the belief that famed poet Paul Laurence Dunbar went to Steele High School. He graduated from Central High School in 1891. Steele High School didn’t open until 1894. When Central closed, all of the records were transferred to Steele, and that is how the error occurred, he explained.

Rice said that “when Paul Laurence Dunbar finished high school he couldn’t get a decent job so he became an elevator operator in the Callahan Building, which later became the Gem City building, making $4 a week.”

Black ‘firsts’ in Dayton

Rice uncovered many milestones through the years.

One of the first marriages of Black people was that of Joe Wheeler and Catherine Sills. They made their home on McLain Street As of 1976, one of their descendants still lived in Dayton.

The town’s first Black church, Wayman African Methodist Episcopal, began meeting in a log cabin on the corner of McLain and Potomac Streets in East Dayton. The congregation later moved to Eaker Street and later to Fifth and Bank Streets in West Dayton. Finally, in the 1920s, they moved to Westwood.

Dayton’s first Black-owned bank, Unity State Bank, opened in 1970.

The city’s first Black doctor had the last name of Burns. His office was located on 5th and Perry Streets, and he was the man that told Paul Laurence Dunbar that he had tuberculosis.

The first Black druggist in the city was LeRoy Cox. The drugstore he owned opened sometime during 1911 or 1912. It was located on Fifth and Charter streets. The drugstore had just opened for business when the Great Flood of 1913 ravaged the region. Cox went to work at the post office carrying mail until 1919, when he reopened for business.

Theaters and restaurants

Up until the early 1920s, Black residents could attend any theater or restaurant in Dayton.

Segregation of public facilities started when the Keith Theatre opened its new building at Fourth and Ludlow streets in 1923, and Black residents were barred from almost all downtown theaters, restaurants and other places. Three restaurants, at Union Station, the bus station and Mose Moore’s on Sixth Street were the only ones still open to Black residents.

Theater segregation remained until 1941, when a group of Black businessmen and clergy fought for an end to the policy. In 1951, similar pressure was applied the the restaurant industry, ending segregation there as well.

In 1926, Black businessmen Carl Anderson and Augustus Giles built the Classic Theater at 817 W. Third St. The Classic Theater opened the next year, in 1927. Rice said silent movies were the first productions at the theater. Entertainers such as Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Count Bassie, Billy Eckstine and the Mills Brothers performed there.

The Palace Theater on the corner of Fifth and Williams streets was founded in 1929 by Dr. Lloyd Cox (who was Black) and Valentine Winters. In 1933, the theater was converted to a nightclub.

Politics

The first Black person elected to office in the Dayton area was Frederick Bowers, a Jefferson Twp. real estate broker who was elected to the Ohio House of Representatives as a Republican in 1949 and again in 1951.

David Albritton, a former Golden Gloves boxer and Olympic athlete, won election to the Ohio House from the same district a short time later. C.J. McLin Jr. was elected to the state legislature in 1967 and served until 1988.

Important homes and places

At 205 Dunbar Ave., the first Black-owned taxicab company, West Side Taxi Co., was started by Jack Spicer.

The Mallory Building, at the corner of Fifth Street and Horace Avenue, was once the home of Robert Mallory, a captain in the Army during World War I. The Queen Anne-style home was built by Black contractors.

A home at 59 Horace Ave. was owned by Mose Moore, who was once the wealthiest Black person in Dayton before the turn of the century. Moore owned a combined restaurant, pool room, hotel and barbershop in downtown Dayton. He died in 1927.

A home on Shannon Street is where Hallie Q. Brown once lived. In the early 1900s, Brown founded the first school for Black adults in Dayton. She later was a professor at Wilberforce University. She died in 1930.

About the Author